Music of Robert Xavier Rodríguez

Jeff Lankov, piano

2:00 p.m. Sunday, October 6, 2013 8:00 p.m. Friday, October 11, 2013

Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall Jonsson Performance Hall, UT Dallas

54 W. 57th Street; New York, NY 800 W. Campbell Rd., Richardson, TX

Tickets $25, CarnegieCharge Tickets $15, Purchase online at

212-247-7800 ah.utdallas.edu/tickets

$20 Seniors and Students UT Dallas Students and Faculty Free

(at Box Office Only) Box Office: 972-883-2552

Box Office at 57th and Seventh

-------------------------------------------------------------

Program

Semi-Suite (1980) for piano, four-hands

The All-Purpose Rag

Limerick

Jig

Tango

The All-Purpose Rag

(Duet with RXR)

Fantasia Lussuriosa (1989)

Estampie (1981)

Istanpitta Ghaetta

Intermezzo

Scherzo

The Slow Sleazy Rag

The Couple Action Rag

Rimbombo

The Reversible Rag

~~~ Intermission ~~~

“Hot Buttered Rumba” from Aspen Sketches (1992)

Seven Deadly Sequences (1990)

Dies Irae/Ave Maria

Pride

Envy

Anger

Sloth

Avarice

Gluttony

Lust/Dies Irae

The Seventh Deadly Soft-Shoe

Caprichos (2012)

El niño, el pájaro, los gatos y el señor Scarlatti

La gallina ciega

La maja des nuda y vestida y otra vez des nuda

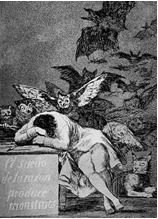

El sueño de la razón produce monstruos

Fandango de los duendecitos

-------------------------------------------------------------

Bios

Robert Xavier Rodríguez is “one of the major American composers of his generation” (Texas Monthly). His music has been described as “Romantically dramatic” (Washington Post), “richly lyrical” (Musical America) and “glowing with a physical animation and delicate balance of moods that combine seductively with his all-encompassing sense of humor” (Los Angeles Times). “Its originality lies in the telling personality it reveals. His music always speaks, and speaks in the composer’s personal language.” (American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters).

Robert Xavier Rodríguez is “one of the major American composers of his generation” (Texas Monthly). His music has been described as “Romantically dramatic” (Washington Post), “richly lyrical” (Musical America) and “glowing with a physical animation and delicate balance of moods that combine seductively with his all-encompassing sense of humor” (Los Angeles Times). “Its originality lies in the telling personality it reveals. His music always speaks, and speaks in the composer’s personal language.” (American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters).

Rodríguez received his musical training in San Antonio (b. 1946), Austin (UT), Los Angeles (USC), Lenox (Tanglewood), Fontainebleau (Conservatoire Américain) and Paris. His teachers have included Nadia Boulanger, Jacob Druckman, Bruno Maderna and Elliott Carter. Rodríguez first gained international recognition in 1971, when he was awarded the Prix de Composition Musicale Prince Pierre de Monaco by Prince Rainier and Princess Grace at the Palais Princier in Monte Carlo. Other honors include the Prix Lili Boulanger, a Guggenheim Fellowship, awards from ASCAP, five NEA grants and the Goddard Lieberson Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Rodríguez has served as Composer-in-Residence with the San Antonio Symphony and the Dallas Symphony. He is currently University Professor at The University of Texas at Dallas, where holds an Endowed Chair in Art and Aesthetic Studies and is Director of the Musica Nova ensemble. He is active as a guest lecturer and conductor.

Rodríguez's works have been performed by conductors such as Sir Neville Marriner, Antal Dorati, Eduardo Mata, James DePriest, Sir Raymond Leppard, Keith Lockhart and Leonard Slatkin and by such organizations as the New York City Opera, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Dallas Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Vienna Schauspielhaus, Israel Philharmonic, Mexico City Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra and the Seattle, Houston, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Baltimore, St. Louis, National, Boston and Chicago Symphonies. His music is published exclusively by G. Schirmer, and seventeen CDs of his music have been recorded on the Newport, Crystal, Orion, Gasparo, Pro Arte, ACA, Urtext, CRI (Grammy nomination), First Edition, Schott, Naxos and Albany labels.

Pianist Jeff Lankov has been described as “alternately ferocious and sensitive” (The New York Times), “a fearless musician” (Dallas Morning News), “a master of concert programming” (Ft. Worth Star-Telegram) and “a pianist of great passion and verve” (Portland Tribune). His solo programs regularly feature works by living composers, often in unusual juxtapositions that explore the synthesis of popular and classical forms. His multimedia programs combine music with theatrical elements, visual art and computer-generated sounds and images. Recent concerts have included the piano works of John Adams, Blind Tom, John Cage, Michael Finnissy, George Gershwin, Scott Joplin and Astor Piazzolla, along with music for toy piano and prepared piano and Lankov’s own solo-piano transcriptions of Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps and The Firebird. This season’s performances will include the complete piano works of John Adams and avant-garde arrangements of compositions by Gershwin, The Beatles and Radiohead.

Pianist Jeff Lankov has been described as “alternately ferocious and sensitive” (The New York Times), “a fearless musician” (Dallas Morning News), “a master of concert programming” (Ft. Worth Star-Telegram) and “a pianist of great passion and verve” (Portland Tribune). His solo programs regularly feature works by living composers, often in unusual juxtapositions that explore the synthesis of popular and classical forms. His multimedia programs combine music with theatrical elements, visual art and computer-generated sounds and images. Recent concerts have included the piano works of John Adams, Blind Tom, John Cage, Michael Finnissy, George Gershwin, Scott Joplin and Astor Piazzolla, along with music for toy piano and prepared piano and Lankov’s own solo-piano transcriptions of Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps and The Firebird. This season’s performances will include the complete piano works of John Adams and avant-garde arrangements of compositions by Gershwin, The Beatles and Radiohead.

Lankov received his Ph.D. in Piano Performance from New York University, where he served on the piano faculty. He also studied with Robert Xavier Rodríguez and for twelve years was Pianist and Assistant Director of the Musica Nova ensemble at the University of Texas. As a solo recitalist, concerto soloist and collaborative pianist, Jeff Lankov has performed in such diverse venues as Carnegie Hall, New York Symphony Space, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Radio City Music Hall, Texas Stadium and Broadway theatres. Lankov has recorded piano works by Gershwin, Piazzolla, Finnissy and Messiaen. He will record this program of Rodríguez’ piano music for Albany Records.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Composer’s Notes

My very first composition, written at age six, was for piano. I hope no one ever finds it. When I began my studies with Nadia Boulanger in 1969, I was a serious young man of 23, writing in an angst-ridden Viennese Expressionist style. Boulanger told me that I would be only half a composer until I also learned to express in my music the same love of laughter that she knew I enjoyed as a person. I eventually got the message, and I think Boulanger would be pleased to see that all of the pieces on this concert, dating from the 80s to the present, incorporate humor in some way.

Semi-Suite (1980) for piano four-hands was a surprise birthday present for my wife, Darlene. The five pieces are modeled after Stravinsky’s two sets of piano duets, written for Serge Diaghilev, with one difficult part and one easy one. Here, the easy secondo plays only a few pitches in each piece: in “The All-Purpose Rag,” there is an ostinato soggetto cavato (literally “carved subject”) spelling my nickname for Darlene, BEDE; in “Limerick,” there are five single notes outlining the rhyme scheme of the limerick (AABBA); in “Jig,” there is one repeated D; and in “Tango” there is an ostinato syncopated BBCD. The last movement is a repeat of “The All-Purpose Rag,” hence its title. There are also versions of Semi-Suite for violin and orchestra, commissioned by Stetson University, and for violin, clarinet, piano and percussion, commissioned by Voices of Change, both with a “Ductia” substituted for the “Limerick.”

Fantasia Lussuriosa(1989), literally “Lust Fantasy,” is a set of variations on the “Lust” theme from my ballet The Seven Deadly Sins, which has two versions: for wind ensemble, commissioned by East Texas State University in 1985, and for orchestra, commissioned by the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra in 1992. The piano Fantasia was commissioned by Hélène Wickett, who gave the premiere performance at the University of Texas at Dallas in 1989. Jeff Lankov gave the first performance of a revised version in 1996, also at UTD, and he edited the present 2011 version, which has a new ending.

The music creates a fusion of elements of blues and jazz with 19th and 20th-Century virtuoso piano techniques. Complex rhythms abound, layered in multiple lines of counterpoint, with voices crossing rapidly between the hands. Of particular inspiration in the piano writing was Schumann’s brilliant Symphonic Etudes. In the original ballet, “Lust” features two intertwining pairs of saxophones, abetted by a whip. As an ironic counterpoint to Lust, the Fantasia includes a quotation from my 1981 Boccaccio-based comic opera Suor Isabella, set to a line from Daniel Dibbern’s libretto: “Sensual indulgence is a sure road to sin and damnation!” I have enjoyed quoting the theme briefly in three other works to invoke lustful associations: in the orchestral Piñata (1991) and in the operas The Old Majestic (1988) and Frida (1991). The harmonic changes also appear in Seven Deadly Sequences (1990), for “Lust,” and Six Maxims de la Rochefoucauld (1991), under the vocal setting of the text, “Jealousy is born with love, but it does not always die with love.” Critical commentary includes, “…an exciting tour-de-force…powerful and shocking…a provocative and fascinating work…” Ernest Kramer, Clavier Companion.

Estampie (1981) is a set of variations on a medieval dance. The original scoring, for orchestra, was commissioned and premiered by the Dallas Ballet. I also made a version for clarinet, cello, piano and percussion for the California E.A.R. Unit at the American Dance Festival. Hélène Wickett commissioned and premiered the present virtuoso transcription for piano solo. In the piano version, there are seven movements:

In “Istanpitta Ghaetta,” the estampie is announced.

A slow “Intermezzo” follows, in which the estampie is embellished with lyrical interludes.

In a complex “Scherzo,” the regular rhythm of the estampie is sharply juxtaposed with disjunct atonal writing. Ragtime rhythms appear, treated with Ars Nova discant and isorhythm techniques in a synthesis of widely disparate styles, after which the estampie reappears.

“The Slow Sleazy Rag,” is a slinky tune based on the arpeggiated accompaniment of the “Intermezzo.” It begins and ends with wistful hints of Wagner, and the middle section is shameless stripper music.

“The Couple Action Rag” follows as a companion piece. The two are slow/fast versions of the same material, as in traditional pavane/gaillard pairings. Here, instead of the court, there are lusty evocations of the cabaret.

A short interlude, “Rimbombo” (“resonance”), states the theme quietly, alternating with echoes of the earlier “Intermezzo.”

In “The Reversible Rag,” the medieval rhythm dissolves into a four-note bass figure which expands into a twelve-note row, then shrinks back to the original four notes in mirror fashion. Over this accompaniment, a lopsided atonal rag appears, also in palindrome form, slightly out of phase with the bass. The work ends in a grand quodlibet in which “The Reversible Rag,” “The Couple Action Rag” and the original estampie are played simultaneously. Critical commentary includes, “…glows with a physical animation and delicate balance of moods that combine seductively with his all-encompassing sense of humor…a delightful interplay of rollicking rhythms and dissonant fragmentation that drew upon a Medieval refrain, ragtime colorings and a chilly serial melancholy. Strains of Scott Joplin were filtered through the jazzy Berlin sleaze of Kurt Weill or the eccentric whimsy of Erik Satie to create a poetic drama that teetered over the brink into a frenzied jamboree.” Colin Gardner, Los Angeles Times.

“Hot Buttered Rumba” is the last movement of the Aspen Sketches (1992). The four-movement suite was commissioned for a private concert at a nephrologists’ conference in Aspen that same year. Hélène Wickett gave the premiere performance. The Pacific Symphony commissioned an orchestral version in 1996. Festive and light-hearted, Hot Buttered Rumba employs the popular Afro-Cuban dance rhythm: accents on one, four and seven in an eight-beat pattern. The musical language is tonal, with variations on two short related themes -- one in major key, one in minor – both based on affectionate evocations of traditional rumba rhythmic and melodic motifs. In a contrasting middle section, the driving rumba rhythm begins to waver, in a playful depiction of the intoxicating influence of the celebrated beverage which gives the work its title: hot buttered rum, “the drink that makes you see double and feel single.” After more tipsy rhythmic wobbles and a gleeful glissando outburst, the rumba regains its former footing and roars to a brilliant conclusion. Critical commentary includes, “…Six effervescent minutes of Cuban dance energy… a little tipsy… with its bright Bernsteinian harmonies, its supple Latin dance rhythms and its controlled sexy dynamic swells and retards. There is a good deal of hidden skill to making a piece like this, and also to making it work in performance… pure joy.” Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times.

Seven Deadly Sequences(1990) was commissioned for a dance segment in Fred Curchack’s theatrical production, Sexual Mythology, Part II, based on Dante’s Purgatorio. I gave the first performance at the University of Texas at Dallas. A stern introduction intones two melodies from Gregorian chant: the Dies Irae and the Ave Maria. Each of the Seven Deadly Sins is then depicted, including or followed by a short musical reference to the punishment for each sin, as described by Dante: Pride – broken on the wheel; Envy – put in freezing water; Anger – dismembered alive; Sloth – thrown in snake pits; Greed – put in cauldrons of boiling oil; Gluttony – forced to eat rats, toads and snakes; Lust – smothered in fire and brimstone. Lust leads to a repetition of the Dies Irae. The final Seventh Deadly Soft-Shoe takes one last, irreverent, look at the sins, with a fleeting reference to the Ave Maria. The score contains the performance option to “repeat throughout eternity.”

Caprichos is a set of five virtuoso pieces inspired by paintings and etchings by Francisco Goya (1746-1828). The first three short pieces are based on Goya’s early Neo-Classical paintings on aristocratic subjects for the Spanish court. The last two longer movements are based on Goya’s later revolution-era collection of eighty grotesquely satirical etchings, Los Caprichos (1799). I completed my Caprichos in the summer of 2012 during residencies at the American Academy in Rome and at the Copland House in Peekskill, New York.

The first movement, “El niño, el pájaro, los gatos y el señor Scarlatti” (The Boy, the Bird, the Cat and Mr. Scarlatti), is based on Goya’s portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga as a child. The boy wears a red suit, and he holds a magpie on a string. In the dark, behind the boy, are the bright eyes of three cats greedily watching the bird. Since Domenico Scarlatti had worked at the Spanish court shortly before Goya, I chose Scarlatti’s keyboard Sonata in E Major to set the musical scene. I made no direct quotations, but I based my themes on the rhythms and contours of Scarlatti’s short, repeated motifs and followed his tight, binary structure. There are cinematic depictions of the innocent child, the chirping bird and the predatory cats. Some violence in the middle section suggests what would have happened if the cats had had their way, but the high bird sounds at the end show that the magpie remains safe, albeit a little nervous.

The first movement, “El niño, el pájaro, los gatos y el señor Scarlatti” (The Boy, the Bird, the Cat and Mr. Scarlatti), is based on Goya’s portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga as a child. The boy wears a red suit, and he holds a magpie on a string. In the dark, behind the boy, are the bright eyes of three cats greedily watching the bird. Since Domenico Scarlatti had worked at the Spanish court shortly before Goya, I chose Scarlatti’s keyboard Sonata in E Major to set the musical scene. I made no direct quotations, but I based my themes on the rhythms and contours of Scarlatti’s short, repeated motifs and followed his tight, binary structure. There are cinematic depictions of the innocent child, the chirping bird and the predatory cats. Some violence in the middle section suggests what would have happened if the cats had had their way, but the high bird sounds at the end show that the magpie remains safe, albeit a little nervous.

Goya’s “La gallina ciega”(Blind Man’s Bluff) is a colorful scene of elegantly dressed young men and women at play. A blindfolded young man is surrounded by a ring of his friends, and the mood is of excited conviviality. In the music, the left hand does the chasing, with relentless figuration punctuated with staccato accents. The right hand has a legato counter melody, which teases and playfully eludes the left hand as it makes devious turns up and down the piano’s registers. The chase becomes increasingly rowdy and physical and ends with an exuberant “Gotcha!

Goya’s “La gallina ciega”(Blind Man’s Bluff) is a colorful scene of elegantly dressed young men and women at play. A blindfolded young man is surrounded by a ring of his friends, and the mood is of excited conviviality. In the music, the left hand does the chasing, with relentless figuration punctuated with staccato accents. The right hand has a legato counter melody, which teases and playfully eludes the left hand as it makes devious turns up and down the piano’s registers. The chase becomes increasingly rowdy and physical and ends with an exuberant “Gotcha!

“La maja desnuda, vestida y otra vez desnuda” (The Maja Naked, Clothed and then Naked Again) is based on Goya’s two paintings of the same mysterious woman (or maja) reclining on a bed. In one painting, the maja is fully clothed; in the other, she is naked. In my musical setting, the languorous maja theme is first heard in its naked, single-line simplicity. After a counter-melody, perhaps depicting the viewer, the theme returns and is gradually “dressed” with increasingly rich canons and variations, sometimes with the counter melody superimposed over it. After all the decorations are in place and a musical climax is reached, all the clothes suddenly disappear, and at the end, the theme is

again naked, as it was at the beginning.

“La maja desnuda, vestida y otra vez desnuda” (The Maja Naked, Clothed and then Naked Again) is based on Goya’s two paintings of the same mysterious woman (or maja) reclining on a bed. In one painting, the maja is fully clothed; in the other, she is naked. In my musical setting, the languorous maja theme is first heard in its naked, single-line simplicity. After a counter-melody, perhaps depicting the viewer, the theme returns and is gradually “dressed” with increasingly rich canons and variations, sometimes with the counter melody superimposed over it. After all the decorations are in place and a musical climax is reached, all the clothes suddenly disappear, and at the end, the theme is

again naked, as it was at the beginning.

Goya originally intended “El sueño de la razón”(The Sleep of Reason) to be the first etching in Los Caprichos. The accompanying text reads, “La fantasía abandonada de la razón, produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus maravillas.”(Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with reason, imagination is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders). The etching shows Goya himself asleep at his desk as terrifying creatures rise around him. At first, the music is tranquil and sweetly tonal. Gradually, it grows more and more agitated until it explodes in a violent atonal frenzy. The themes are transformed with increasing rhythmic complexity from one episode to the next in a musical recreation of the way characters in a nightmare imperceptibly change forms and identities. At the height of the terrors, “Reason” awakens, and the peaceful opening material suddenly returns. At the close, however, there remain quiet, unsettling echoes of the dream monsters.

Goya originally intended “El sueño de la razón”(The Sleep of Reason) to be the first etching in Los Caprichos. The accompanying text reads, “La fantasía abandonada de la razón, produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus maravillas.”(Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with reason, imagination is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders). The etching shows Goya himself asleep at his desk as terrifying creatures rise around him. At first, the music is tranquil and sweetly tonal. Gradually, it grows more and more agitated until it explodes in a violent atonal frenzy. The themes are transformed with increasing rhythmic complexity from one episode to the next in a musical recreation of the way characters in a nightmare imperceptibly change forms and identities. At the height of the terrors, “Reason” awakens, and the peaceful opening material suddenly returns. At the close, however, there remain quiet, unsettling echoes of the dream monsters.

The final movement, “Fandango de los duendecitos” (Fandango of the Hobgoblins), is based on Goya’s etching “Duendecitos,” with the text, “Esta ya es otra gente: alegres, juguetones, serviciales; un poco golosos, amigos de pegar chascos; pero muy hombrecitos de bien” (Now this is another kind of people: happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men). Goya’s image is considerably darker than his lighthearted text. He shows three grotesque creatures with giant hands and big, sharp teeth in the act of stuffing themselves. I chose to depict the hobgoblins not just eating, but also dancing a wild fandango. The musical material includes a playfully twisted fandango by Goya’s contemporary W.A. Mozart. The dance appears in Act III of his opera The Marriage of Figaro, set in Spain, to accompany a scene of sexual intrigue. Mozart’s fandango is heavily disguised for most of the piece, with hints of the original melody periodically dropped. The Mozart is revealed in its original form only for a few bars in the middle of the movement and again, just for one bar, at the very end.

The final movement, “Fandango de los duendecitos” (Fandango of the Hobgoblins), is based on Goya’s etching “Duendecitos,” with the text, “Esta ya es otra gente: alegres, juguetones, serviciales; un poco golosos, amigos de pegar chascos; pero muy hombrecitos de bien” (Now this is another kind of people: happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men). Goya’s image is considerably darker than his lighthearted text. He shows three grotesque creatures with giant hands and big, sharp teeth in the act of stuffing themselves. I chose to depict the hobgoblins not just eating, but also dancing a wild fandango. The musical material includes a playfully twisted fandango by Goya’s contemporary W.A. Mozart. The dance appears in Act III of his opera The Marriage of Figaro, set in Spain, to accompany a scene of sexual intrigue. Mozart’s fandango is heavily disguised for most of the piece, with hints of the original melody periodically dropped. The Mozart is revealed in its original form only for a few bars in the middle of the movement and again, just for one bar, at the very end.

— Robert Xavier Rodríguez