Bachanale (1999)

Concertino for Orchestra

Duration: 20 minutes

3(pic)3(ca)3(bc)3(cb)/4331/timp.3perc/hp.2pf/str

version for two pianos (movements I, IV and V) available

Commissioned by the San Antonio Symphony

Premiere Performance: May, 1999, San Antonio Symphony;

Christopher Wilkins, Conductor

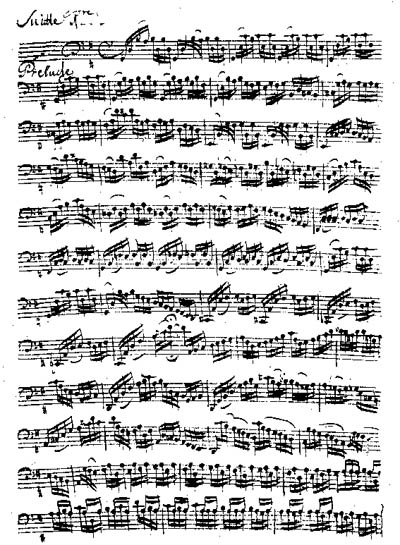

Autograph of J.S. Bach’s Prelude from Cello Suite in G

Review:

Review:

Bach-to-Bach Concerts Spice Symphony Flavor

..With its fine balance of sensual and intellectual pleasures, Bachanale may be the strongest work yet to issue from the witty, passionate, empathic and slightly perverse mind of Rodríguez, a San Antonio native whose music is loved around the world. The entire work grows from the controlled collision of two ideas. The first is the prelude from J.S. Bach’s Cello Suite in G, quoted in a variety of instrumentations...Laid on top of the Bach is an original theme that is syncopated and asymmetrical, counted in seven. Bach’s music is regular as clockwork and counted in four. Think of two gears turning at different speeds: When the seven-beat gear has made four full revolutions, the four-beat gear has made seven revolutions, and the process starts over again, usually with a change in orchestral colors and textures. Thus the whole... five-movement piece is unified by a remarkable rhythmic groove, flexible and always shifting in its small details, yet constant in its overall shape.

But “Bachanale” is music, not mathematics, and the ear was… always delighted by the composer’s virtuosity as an orchestrator... The first movement is subdued and misty, the orchestra limited to piano, harpsichord, harp and strings... The second and third, in which various groups of instruments take their turns through the gears, are brilliantly colored with woodwinds, brass and percussion. This music is sometimes a riot of hootchy-kootchy swiveling, sometimes wonderfully rich and subtle, as in a passage where the violins divide into 17 parts. The calm, lyrical fourth movement evokes a starry summer night. The finale is a wild samba [Samba da Gamba, based on Bach’s Gamba Sonata in G]...

Mike Greenberg, San Antonio Express-News

Program Note:

Rodríguez’ Bachanale: Concertino for Orchestra (1999) was commissioned by the San Antonio Symphony, Christopher Wilkins, Conductor, and premiered in May, 1999. The work is scored for large orchestra: piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contra bassoon, brass, timpani, three percussion, two keyboards, harp and strings.

Rodríguez’ use of the title, Concertino, rather than the more formal Concerto for Orchestra, denotes a shorter and more playful work than the weightier 20th-Century essays in the genre by Bartok, Lutoslawski, Carter, Piston, Hindemith and others. Like Bartok and Lutoslawski, Rodríguez has cast his work in five movements. Each has a fanciful descriptive title:

I. Die Brücke über dem Bach (The Bridge over the Brook) is a modern musical “bridge” over the music of J.S. Bach (“Bach” meaning “brook” in German). The “Bridge” consists of a dance-like, syncopated phrase in 7/8 time for harp, piano and pizzicato strings, which is repeated, with variations, in a rhythmic ostinato throughout the movement. Under the Bridge flows a quotation of the entire first movement of Bach’s Suite in G Major BWV 1007 for solo cello, played in 4/4 time on the harpsichord. Each bar of the Bach is played twice: in its original register, then repeated up an octave in what the composer calls “an instant musical xerox copy,” thus creating an echo effect. The resultant fusion of rhythms and styles recalls Rodríguez’ earlier Les Niais Amoureux (1987) and, particularly, his Sinfonía à la Mariachi (1997), in which mariachi and 18th-Century classical sounds clash and eventually unite.

II. Die Brücke geschmückt (The Decorated Bridge) is a series of virtuoso variations on the opening Bridge music played, in turn, by each instrument of the orchestra. The variations are continuous and are arranged in traditional score order, from the highest to the lowest-pitched members of each instrumental family: woodwinds, brass, percussion and strings. Occasional splashes of Bach’s Brook music also appear from time to time, as each instrument passes in review to place its musical Decorations on the Bridge.

III. In Noch einmal über die Brücke (Once More over the Bridge), the opening movement is repeated in a different orchestration. This time Bach’s Brook music is heard, finally, in its original cello timbre, echoed by violas. There is also more traffic over the Bridge, as the chamber instrumen-tation of the first movement is expanded to include the entire symphony orchestra, playing, for the first time, all together.

IV. A brief interlude follows, based on a repeated motif of rising and falling fifths reminiscent of string tunings. Over the fifths, solo bassoons, oboe, violin and cello answer back and forth in quiet, lyrical phrases. As in the first and third movements, there is extensive imitation at the octave, hence the title, Ecco l’Eco (There’s an Echo). At the end, the Bridge music reappears quietly.

V. Samba da Gamba is built upon another Bach string work, his Sonata in G-Major BWV 1027 for viola da gamba and harpsichord. Bach’s sonata is transformed into a rollicking samba in a modern marriage of the Afro-Caribbean dance form and the festive textures of Bach’s brilliant orchestral suites. Like the last movements of Rodríguez’ Estampie (1981) and Sinfonía à la Mariachi and Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Samba da Gamba is a quodlibet in which all of the work’s principal themes are played simultaneously. At the end, there is one last pensive look at the Decorations on the Bridge before the Bachanale roars to a close.