Caprichos (2012)

for piano solo

Duration: 20 minutes

Premiere Performance: October 6, 2013; Jeff Lankov, Piano

Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall

Review:

…uniquely chilling and nightmarish, yet always with a life-affirming joy in the storytelling itself…a fascinating, thorny, and demanding work…Drawing from a variety of musical resources (including fitting references to Scarlatti and Mozart), it is unquestionably fresh and new, a valuable addition to the piano literature…

Rorianne Schrade, New York Concert Review

Composer Notes:

Caprichos is a set of five virtuoso pieces inspired by paintings and etchings by Francisco Goya (1746-1828). The first three short pieces are based on Goya’s early Neo-Classical paintings on aristocratic subjects for the Spanish court. The last two longer movements are based on Goya’s later revolution-era collection of eighty grotesquely satirical etchings, Los Caprichos (1799). I completed my Caprichos in the summer of 2012 during residencies at the American Academy in Rome and at the Copland House in Peekskill, New York.

The first movement, “El niño, el pájaro, los gatos y el señor Scarlatti” (The Boy, the Bird, the Cat and Mr. Scarlatti), is based on Goya’s portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga as a child. The boy wears a red suit, and he holds a magpie on a string. In the dark, behind the boy, are the bright eyes of three cats greedily watching the bird. Since Domenico Scarlatti had worked at the Spanish court shortly before Goya, I chose Scarlatti’s keyboard Sonata in E Major to set the musical scene. I made no direct quotations, but I based my themes on the rhythms and contours of Scarlatti’s short, repeated motifs and followed his tight, binary structure. There are cinematic depictions of the innocent child, the chirping bird and the predatory cats. Some violence in the middle section suggests what would have happened if the cats had had their way, but the high bird sounds at the end show that the magpie remains safe, albeit a little nervous.

The first movement, “El niño, el pájaro, los gatos y el señor Scarlatti” (The Boy, the Bird, the Cat and Mr. Scarlatti), is based on Goya’s portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga as a child. The boy wears a red suit, and he holds a magpie on a string. In the dark, behind the boy, are the bright eyes of three cats greedily watching the bird. Since Domenico Scarlatti had worked at the Spanish court shortly before Goya, I chose Scarlatti’s keyboard Sonata in E Major to set the musical scene. I made no direct quotations, but I based my themes on the rhythms and contours of Scarlatti’s short, repeated motifs and followed his tight, binary structure. There are cinematic depictions of the innocent child, the chirping bird and the predatory cats. Some violence in the middle section suggests what would have happened if the cats had had their way, but the high bird sounds at the end show that the magpie remains safe, albeit a little nervous.

Goya’s “La gallina ciega”(Blind Man’s Bluff) is a colorful scene of elegantly dressed young men and women at play. A blindfolded young man is surrounded by a ring of his friends, and the mood is of excited conviviality. In the music, the left hand does the chasing, with relentless figuration punctuated with staccato accents. The right hand has a legato counter melody, which teases and playfully eludes the left hand as it makes devious turns up and down the piano’s registers. The chase becomes increasingly rowdy and physical and ends with an exuberant “Gotcha!

Goya’s “La gallina ciega”(Blind Man’s Bluff) is a colorful scene of elegantly dressed young men and women at play. A blindfolded young man is surrounded by a ring of his friends, and the mood is of excited conviviality. In the music, the left hand does the chasing, with relentless figuration punctuated with staccato accents. The right hand has a legato counter melody, which teases and playfully eludes the left hand as it makes devious turns up and down the piano’s registers. The chase becomes increasingly rowdy and physical and ends with an exuberant “Gotcha!

“La maja desnuda, vestida y otra vez desnuda” (The Maja Naked, Clothed and then Naked Again) is based on Goya’s two paintings of the same mysterious woman (or maja) reclining on a bed. In one painting, the maja is fully clothed; in the other, she is naked. In my musical setting, the languorous maja theme is first heard in its naked, single-line simplicity. After a counter-melody, perhaps depicting the viewer, the theme returns and is gradually “dressed” with increasingly rich canons and variations, sometimes with the counter melody superimposed over it. After all the decorations are in place and a musical climax is reached, all the clothes suddenly disappear, and at the end, the theme is

again naked, as it was at the beginning.

“La maja desnuda, vestida y otra vez desnuda” (The Maja Naked, Clothed and then Naked Again) is based on Goya’s two paintings of the same mysterious woman (or maja) reclining on a bed. In one painting, the maja is fully clothed; in the other, she is naked. In my musical setting, the languorous maja theme is first heard in its naked, single-line simplicity. After a counter-melody, perhaps depicting the viewer, the theme returns and is gradually “dressed” with increasingly rich canons and variations, sometimes with the counter melody superimposed over it. After all the decorations are in place and a musical climax is reached, all the clothes suddenly disappear, and at the end, the theme is

again naked, as it was at the beginning.

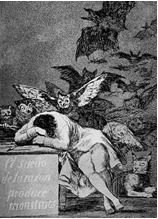

Goya originally intended “El sueño de la razón”(The Sleep of Reason) to be the first etching in Los Caprichos. The accompanying text reads, “La fantasía abandonada de la razón, produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus maravillas.”(Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with reason, imagination is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders). The etching shows Goya himself asleep at his desk as terrifying creatures rise around him. At first, the music is tranquil and sweetly tonal. Gradually, it grows more and more agitated until it explodes in a violent atonal frenzy. The themes are transformed with increasing rhythmic complexity from one episode to the next in a musical recreation of the way characters in a nightmare imperceptibly change forms and identities. At the height of the terrors, “Reason” awakens, and the peaceful opening material suddenly returns. At the close, however, there remain quiet, unsettling echoes of the dream monsters.

Goya originally intended “El sueño de la razón”(The Sleep of Reason) to be the first etching in Los Caprichos. The accompanying text reads, “La fantasía abandonada de la razón, produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus maravillas.”(Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with reason, imagination is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders). The etching shows Goya himself asleep at his desk as terrifying creatures rise around him. At first, the music is tranquil and sweetly tonal. Gradually, it grows more and more agitated until it explodes in a violent atonal frenzy. The themes are transformed with increasing rhythmic complexity from one episode to the next in a musical recreation of the way characters in a nightmare imperceptibly change forms and identities. At the height of the terrors, “Reason” awakens, and the peaceful opening material suddenly returns. At the close, however, there remain quiet, unsettling echoes of the dream monsters.

The final movement, “Fandango de los duendecitos” (Fandango of the Hobgoblins), is based on Goya’s etching “Duendecitos,” with the text, “Esta ya es otra gente: alegres, juguetones, serviciales; un poco golosos, amigos de pegar chascos; pero muy hombrecitos de bien” (Now this is another kind of people: happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men). Goya’s image is considerably darker than his lighthearted text. He shows three grotesque creatures with giant hands and big, sharp teeth in the act of stuffing themselves. I chose to depict the hobgoblins not just eating, but also dancing a wild fandango. The musical material includes a playfully twisted fandango by Goya’s contemporary W.A. Mozart. The dance appears in Act III of his opera The Marriage of Figaro, set in Spain, to accompany a scene of sexual intrigue. Mozart’s fandango is heavily disguised for most of the piece, with hints of the original melody periodically dropped. The Mozart is revealed in its original form only for a few bars in the middle of the movement and again, just for one bar, at the very end.

The final movement, “Fandango de los duendecitos” (Fandango of the Hobgoblins), is based on Goya’s etching “Duendecitos,” with the text, “Esta ya es otra gente: alegres, juguetones, serviciales; un poco golosos, amigos de pegar chascos; pero muy hombrecitos de bien” (Now this is another kind of people: happy, playful, obliging; a little greedy, fond of playing practical jokes; but they are very good-natured little men). Goya’s image is considerably darker than his lighthearted text. He shows three grotesque creatures with giant hands and big, sharp teeth in the act of stuffing themselves. I chose to depict the hobgoblins not just eating, but also dancing a wild fandango. The musical material includes a playfully twisted fandango by Goya’s contemporary W.A. Mozart. The dance appears in Act III of his opera The Marriage of Figaro, set in Spain, to accompany a scene of sexual intrigue. Mozart’s fandango is heavily disguised for most of the piece, with hints of the original melody periodically dropped. The Mozart is revealed in its original form only for a few bars in the middle of the movement and again, just for one bar, at the very end.