De Rerum Natura (2013)

Tone Poem for Orchestra, based on Lucretius’ Latin poem (1st Century, B.C.)

Duration: 27 minutes

Orchestra: 2(pic).1+ca.2.2/4.2.2+btbn.0/timp.2perc/pf.hp/str

Commissioned by the University of Texas at Dallas

for the opening of the Edith O’Donnell Arts & Technology Building

Premiere Performance November, 9, 2013

Musica Nova Orchestra, RXR Conductor

Reviews:

Music is about emotions, so we tend to forget that composers are also thinkers. The contemporary American composer Robert Xavier Rodriguez has poured a wealth of thought into a 27-minute orchestral work based on the ancient Roman philosopher and poet Lucretius, who had an enormous influence on Western civilization through his book-length poem “On the Nature of Things” (De rerum natura). Rodriguez’s piece…musically depicts Lucretius’s themes of “reason, beauty, and pleasure.”

The composer’s descriptions are both heady and detailed—the fourth movement, for example, is titled “Variations: Skolion of Seikilos (. . . loosening our bonds).” It is meant to express Lucretius’s rejection of eternal reward and damnation in favor of a belief that after death we dissolve back into the atoms that create the stars…What the listener hears in Rodriguez’s piece is dense, varied, largely tonal, and dynamic. The perpetually restless movement of Nature awed Lucretius, and this music is almost always restless. Modeling his format on Bernstein’s Serenade, where each movement depicts a guest at the banquet immortalized in Plato’s Symposium, Rodriguez gives voice to two philosophers, Lucretius as a violin and Epicurus as a cello… There’s no doubting his skill and invention, and the eclectic sound world of De Rerum Natura, which includes a samba at the end (a nod to a Latin writer from today’s Latin culture) is full of color, atmosphere, and memorable motifs.

Huntley Dent, Fanfare Magazine

…dreamy, liquescent, scintillating music that grows in intensity…Overlapping brass fanfares and dialogues between solo violin and cello become recurrent gestures as the work proceeds...this is appealing music, almost cinematic, smartly orchestrated.

Scott Cantrell, The Dallas Morning News

…terrific work…a most attractive piece… Rodríguez writes in a neo-romantic musical language, with neo and romantic offered in equal portions…The finale was suitably exciting, and even offered some “big-band” sounds in the brass…Additionally, this work uses a solo violin and cello to great effect, and adding the harp to the combination was lovely…a perfect 10.

Gregory Sullivan Isaacs, TheaterJones.com

Composer Note:

De Rerum Natura (2013) is a 27-minute orchestral tone poem commissioned by the University of Texas at Dallas for the opening of the Edith O'Donnell Arts and Technology Building. In keeping with the themes of Art and Technology, I based the music on De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) by the Roman poet Lucretius (first century B.C.). The Latin poem is a sweeping treatise on both science and the arts. In The Swerve, Stephen Greenblatt calls De Rerum Natura “a strikingly modern understanding of the world… a vision of atoms randomly moving in an infinite universe—imbued with a poet’s sense of wonder. Wonder did not depend on the dream of an afterlife; in Lucretius it welled up out of a recognition that we are made of the same matter as the stars and the oceans and all things else. And this recognition was the basis for the way he thought we should live—not in fear of the gods, but in pursuit of pleasure…”

In my De Rerum Natura, I followed the model of Leonard Bernstein’s 1954 Serenade for violin and orchestra, based on the Symposium of Plato. Like Bernstein, instead of making a vocal setting of the text, I have created instrumental music that expresses ideas in the text. Since Lucretius’ poem is in six “books,” there are six movements, played without pause. Each movement has a subtitle taken from the poem. I included incidental solos for violin and cello: the cello representing Lucretius and the violin representing Lucretius’ hero, Epicurus, the Greek philosopher of the third century B.C. who taught that pleasure and pain are the only valid measures of good and evil.

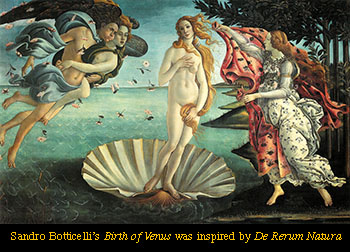

I. Invocation of Venus (“…the place of fierce desire”). Lucretius begins De Rerum Natura with a sensuous hymn of praise to the Goddess of Love and to the joys of sexual experience. Botticelli’s celebrated painting The Birth of Venus was inspired by this passage. The music opens with a passionate “desire” motive and builds to an ecstatic climax, followed by floating lines from the solo violin and cello.

II. Ricercare (“…where the mind soars at liberty”) expresses Lucretius’ secular humanist celebration of the intellect. As Greenblatt puts it, for Lucretius, “There is no master plan, no divine architect, no intelligent design. Nature restlessly experiments, and we are simply one among the innumerable results…” Here, the cello solo introduces a musical version of scientific inquiry. A traditional Lydian scale of seven pitches is established. Suddenly, an eighth pitch arrives from outside the system. The new pitch is pondered and then assimilated to create a new scale. Increasingly more complex harmony and counterpoint follow as the sequence moves through new pitches and keys. The “desire” motif from the previous movement drives the exploration forward until the complete spectrum of all twelve pitches is united in a powerful four-fold “Eureka!” outburst.

III. Variations: Skolion of Seikilos (“…loosening our bonds”) deals with one of Lucretius’ central themes: conquering the fear of death by rejecting the idea of eternal rewards or damnation and embracing, instead, a peaceful return to the elements from which we came. As Greenblatt writes, “When we look up at the night sky and marvel at the numberless stars, we are not seeing the handiwork of the gods or a crystalline sphere. We are seeing the same material world of which we are a part and from whose elements we are made… That is all; but it is enough.” To represent death, I chose the earliest known example of Western music, a Greek song from 200 B.C. in Mixolydian mode written on a tombstone with the philosophical text, “Shine as long as you live. Do not grieve. Life is short. Time demands its end.” The theme is stated in canon, with a tolling bell, followed by variations. The variations are pensive at first, then increasingly violent, depicting the terrors of death. The music reaches a tense climax and then drifts into a quiet coda marked by distant chimes.

IV. Scherzo (“…atoms that touch the senses with pleasure”). Lucretius takes delight in extoling each of the five human senses. Rather than depicting the senses one at a time, I use both bowed and pizzicato strings with harp, piano and percussion accents to induce a general sensory tickling. The music bounces between a jig (in 12/8 time) and a slip-jig (in 9/8 time), with a roller-coaster fluctuation of dynamics between soft and loud. There is a woodwind interlude, as in the famous scherzo pizzicato from Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony, but instead of stopping, the strings continue in tremolo pizzicato, accompanying the winds as they play in lyrical pairs. When the winds have finished, the strings go on with their jig.

V. Fanfare & Cadenza (“…the swerve”). Lucretius believed in the importance of chance in the process of creation. Greenblatt says, “The stuff of the universe, Lucretius proposed, is an infinite number of atoms moving randomly through space, like dust motes in a sunbeam, colliding, hooking together, forming complex structures, breaking apart again, in a ceaseless process of creation and destruction.” In this movement, there are three unexpected events (or “swerves,” as Lucretius calls them): First, a brass fanfare bursts in to interrupt the Scherzo. A pounding C-sharp pedal point begins in the trombones and timpani and rises in the strings, culminating in wild horn and trumpet rips. In a second “swerve,” the intensity suddenly cools, the repeated note switches to a quiet E-flat in the harp, the strings float upward, and gentler woodwinds take the place of the brass. In a final “swerve,” the solo cello breaks into a cadenza, joined by the violin, with virtuoso variations on the previous Scherzo.

VI. Finale (“…heralds of godlike beauty”) expresses Lucretius’ joy in the arts as the perfect embodiment of his philosophy of reason, beauty and pleasure. The movement opens with a glowing reminiscence of the opening Invocation of Venus. Gradually, the music becomes more rhythmic, in keeping with Lucretius’ characterization of the universe as “speeding… in endless dance,” and a driving samba emerges. As the samba builds, led by the “desire” motif, the Ricercare, the jig, the Skolion (now triumphant) and other themes from the work whirl around merrily together to create, in honor of Lucretius, literally, a “Latin celebration.”