Forbidden Fire (1998)

Cantata for the Next Millennium

for Bass-Baritone, Double Chorus and Orchestra

Duration: 22 minutes

3(3pic)222/4331/timp.3perc/hp.pf/str

Piano reduction available

Commissioned by the University of Miami School of Music

Premiere Performance: October, 1998;

University of Miami Chorus and Orchestra; George Cordes, Bass-Baritone;

Thom M. Sleeper, Conductor

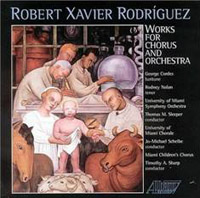

Recording: Robert Xavier Rodríguez Works for Chorus and Orchestra,

Albany, TROY 430

University of Miami Symphony Orchestra and Chorus;

Thom M. Sleeper, Conductor

Review:

Mystery plays out well at Symphony

...iridescent colorations, highly complex textures, cinematic breadth... “Forbidden Fire” weaves quotations from Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” through a thick garden of other poetic and sacred texts. Rodríguez also uses musical quotations from the last string quartet of Beethoven, the most Promethean of all composers. The music is often intensely dramatic... yearningly lyrical and consistently ingenious in the way the Beethoven quotes are expanded, shaded and integrated into Rodríguez’s original material.

Mike Greenberg, San Antonio Express-News

Program Note:

Conceived as a companion piece to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Forbidden Fire explores dangerous or forbidden knowledge, as represented by the Promethean metaphor of stealing fire from the gods. Fragments of works by Aeschylus, Lucretius, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Blake, Schiller, Beethoven, Percy Shelley, Mary Shelley and Edna St. Vincent Millay are intercut with writings from an Egyptian temple, the Bhagavad Gita and the Bible to trace the exhilaration as well as the serious consequences of man’s eternal quest for knowledge.

In Forbidden Fire the bass-baritone soloist personifies the seeker of secret truth. His part, primarily taken from the words of Mary Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, expresses the fearless optimism of one who is determined to seize the fire. The two choruses, on the other hand, offer more complex reactions to his quest. Sometimes they echo him; sometimes they cheer him on; sometimes they warn of disastrous results, as in Robert Oppenheimer’s words at the first testing of the atomic bomb, “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” More often, the choruses express contrasting aspects of the same scene, as in the simultaneous settings of William Blake’s two visions of the industrial age: “Tyger, tyger burning bright” and, appropriately for recent cloning technology, “Little lamb, who made thee?”. While Beethoven’s setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy embraces a better world where “all men will be brothers,” Rodríguez’ Forbidden Fire celebrates the utopian ideal of man’s mastery, not only of the secrets of life and death, but of what Beethoven expressed in his diary as humanity’s ultimate challenge, “O God, give me the strength to conquer myself!” Beethoven’s words are sung at the work’s climax and at its close.

In Forbidden Fire the bass-baritone soloist personifies the seeker of secret truth. His part, primarily taken from the words of Mary Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein, expresses the fearless optimism of one who is determined to seize the fire. The two choruses, on the other hand, offer more complex reactions to his quest. Sometimes they echo him; sometimes they cheer him on; sometimes they warn of disastrous results, as in Robert Oppenheimer’s words at the first testing of the atomic bomb, “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” More often, the choruses express contrasting aspects of the same scene, as in the simultaneous settings of William Blake’s two visions of the industrial age: “Tyger, tyger burning bright” and, appropriately for recent cloning technology, “Little lamb, who made thee?”. While Beethoven’s setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy embraces a better world where “all men will be brothers,” Rodríguez’ Forbidden Fire celebrates the utopian ideal of man’s mastery, not only of the secrets of life and death, but of what Beethoven expressed in his diary as humanity’s ultimate challenge, “O God, give me the strength to conquer myself!” Beethoven’s words are sung at the work’s climax and at its close.

Musically, Forbidden Fire reflects its Beethovenian roots. At the intervallic core (or what Rodríguez calls “the musical DNA”) of the work are two three-note motives from Beethoven’s last String Quartet, Op. 135. In the cantata, as well as in the quartet, the two motives are set to Beethoven’s fateful question and answer, Muss es sein? (Must it be?) Es muss sein. (It must be.). Two additional quotations from the quartet are a fiery ostinato passage from the development of the scherzo and the cantante e tranquillo opening of the slow movement.

Unified by Beethoven’s two motives, the five movements of Forbidden Fire cast the same musical material into five different textures:

(I) impressionistically wistful at the beginning to depict the mysteries of the

universe (All that is, all that was, and all there is to be...);

(II) intense and agitated at man’s defiance of the gods by taking the fire into his

own hands (Now men are masters of their minds!);

(III) serenely tonal in quiet awareness of his new power (O brave new world...);

(IV) heroically rising to the challenge of controlling his own destiny

(Bring me my chariot of fire!); then

(V) ending in a glistening synthesis of styles as baritone and chorus sing

Schiller’s

ecstatic Homage to the Arts (No bonds can hold, no bounds

can stay my flight. My endless realm is thought, my throne is light...).