La L’Arc-en-ciel d’Arlequin (Harlequin’s Rainbow)

for Mezzo-Soprano & String Quartet (2021)

Based on poems from Albert Giraud’s Pierrot Lunaire

Duration: 38 minutes

Commissioned by the University of Texas at Dallas

Premiere Performance: September 17, 2022

Rachel Calloway, Mezzo-Soprano & Amernet Quartet

Review:

Review:

An artist whose music embraces humor, heavy attention to mood and might be described as ‘romantically dramatic’, Robert Xavier Rodríguez pens a song cycle for mezzo-soprano and string quartet based on poems from Albert Giraud's Pierrot Lunaire… The title track opens the listen with 12 chapters, where Rachel Calloway’s stunning mezzo-soprano soars with an expressive presence as Misha Vitenson and Avi Hagin’s skilled violins, Michael Klotz’s well timed viola and Jason Calloway’s moody cello help cultivate a shifting landscape of exploratory, orchestral dynamics…The listen continues Rodriguez’s position as an animated and creative composer with a sense of humor, and the instrumentation provided by the Amernet Quartet only adds to the appeal of his inimitable vision.

– TAKE EFFECT REVIEWS

Composer's Note:

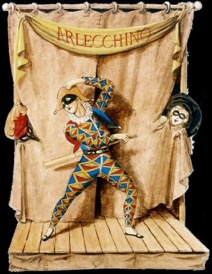

Harlequin’s Rainbow is a companion piece to Arnold Schoenberg’s 1912 Pierrot Lunaire, of the same length, for reciter and chamber ensemble. It also pairs with Schoenberg’s String Quartet No. 2 (1908), which includes voice. In his Pierrot Lunaire, Schoenberg set 21 of Giraud’s 50 poems in a German translation. He chose dark poems with images of death about Pierrot, the sad, white-faced clown from the Italian commedia dell’arte. In L’Arc-en-ciel d’Arlequin, I have set twelve cheerier poems in the original French, mostly about the more extroverted, rainbow-clad character of Harlequin. The sensuous, Symbolist poems express the escapism of theater, the quest of the artist and the mystery of the moon. They conjure the fairy-tale atmosphere of the elegant French pantomime version of the commedia to recount Harlequin’s adventures with the shy Pierrot, as they compete for the love of the beautiful Columbine.

Every poem has the same strict rhyme scheme of three stanzas. The opening couplet returns at the end of the second stanza, and the first line comes again at the end: ABBA/ABAB/ABBAA. Each poem, thus, contains a built-in musical symmetry, which I have followed. I chose four poems which Schoenberg set: Columbine (my no. 5), Mondestrunken (my no. 7), Heimweh (my no. 9) and O Alter Duft (my no. 10). In his Pierrot, Schoenberg avoided any musical parallels to the rhymes or to the recurring words.

My musical language freely mixes tonality and atonality, following the lead of Schoenberg’s pupil Alban Berg. I also feature the octatonic scale of alternating half steps and whole steps that Schoenberg’s musical nemesis, Igor Stravinsky, used in The Rite of Spring in the same year as Pierrot Lunaire. I gain further inspiration from that era by evoking the lush textures of Schoenberg’s French contemporaries Fauré and Debussy and the smoke-filled cabaret harmonies of Kurt Weill.

No. 1, Théâtre (Theater), creates the excitement of the Italian comedy, as the voice thrills to the transporting beauty of theater and introduces the desirable Columbine. A bravura cello solo leads to a short, wistful coda.

No. 2, Décor (Decor), begins with string tremolos and delicate figuration for the swooping wings of the “great birds of purple and gold” which decorate the theater set. The music swells to depict the birds’ graceful flight, and the song closes with the quiet return of the opening ripples.

No. 3, Cuisine Lyrique (Lyrical Cuisine), is a quirky serenade about the lonely Pierrot, gazing at the moon and seeing it as a golden omelet. Marked giocoso misterioso, it begins and ends with a gentle, guitar-like accompaniment of pizzicato strings. The more intense central section describes Pierrot’s fantasy of throwing the omelet into the sky from his frying pan.

No. 4, Harlequinade (Harlequin’s Tale), is a celebration of Harlequin, with cascades of string harmonics depicting the rainbow glow of his signature costume of red, green and yellow patches. Sly, chromatic motives in the strings show Harlequin’s devious, trickster ways, and, with a flash of harmonics, the song ends in a burst of glory.

No. 5, À Colombine (To Columbine), is an erotic expression of longing for the unattainable Columbine. Soaring vocal lines, pungent harmonies and two alternating tempos show the rising waves of emotion as the text expresses an ardent desire, at last, to experience “…the fleeting joy of strewing your auburn hair with the pale flowers of the moonlight.”

No. 6, Arlequin (Harlequin), is a rhythmic scherzo with harmonic surprises, vocal roulades and frequent changes of musical texture. The text parallels Leporello’s aria “Madamina” from Don Giovanni in recounting a seducer’s well-practiced tricks as he pursues his amorous desires.

In No. 7, Ivresse de Lune (Drunk with the Moon), the strings play an indulgently tipsy waltz, as the poet gazes at the moon and sings of “The wine we drink from our eyes.” Voice and strings build to a frenzied, absinth-induced state of ecstasy, and the poet blissfully drifts off to oblivion.

No. 8, Violon du Lune (The Violin of the Moon), is the first of two poems about stringed instruments. The song features delicate string arpeggios with seductive harmonies and a sustained vocal line to create the luminous glow of “the moon, with thin, slow rays.” It radiates, “vibrating in the endless night, the soul of the throbbing violin, full of silence and harmony.”

No. 9, Nostalgie (Nostalgia), returns to the “slow, sentimental Pierrot.” In a swooning tango, Pierrot, inspired by the moon, relentlessly clings to the beloved old traditions of the commedia dell’arte, “the soul of ancient comedies.”

No. 10, Parfum Bergame (Perfumes of Bergamo), evokes the “sweet fragrance of yesterday which intoxicates my senses.” I invoke the twelve-tone system which Schoenberg adopted after Perrot Lunaire by building each song around a different pitch. For this song, I use the order of the songs’ pitch centers (A-flat, E, F-sharp, G, E-flat, B followed, a tritone away, by D, B-flat, C, D-flat, A and F) as a twelve-note row, here wrapped around D-flat. Schoenberg’s atonal setting of the same text (O alter Duft) nostalgically looks back to the world of tonal music, which he was abandoning. In my tonal setting, I nostalgically look back to the world of serial music, which I am not abandoning, but embracing from a post-modern, 21st-century perspective of looking forward while re-connecting with the treasures of the past.

In No. 11, L’Alphabet (The Alphabet), the strings exchange playful, repeated figuration, as the poet recalls his schoolboy recitation of an enchanted alphabet, “with every letter a mask.” The music grows more lyrical, and glowing string arpeggios and harmonics return, as the poet imagines Harlequin, tracing the magical letters “with his rainbow form.”

A gentler continuation of the cello solo from the first song leads to No. 12, Souper sur l’Eau (Soirée on the Water). Again, the text includes a reference to strings, set to a dreamy barcarolle in two tender interludes for the quartet alone. Harlequin, Pierrot and Columbine are in Venice, home of the commedia dell’arte. “Bejeweled with fireflies,” they wine and dine on the water “under a glowing moon,” as “viols sing madrigals in languorous gondolas.”

© Robert Xavier Rodríguez